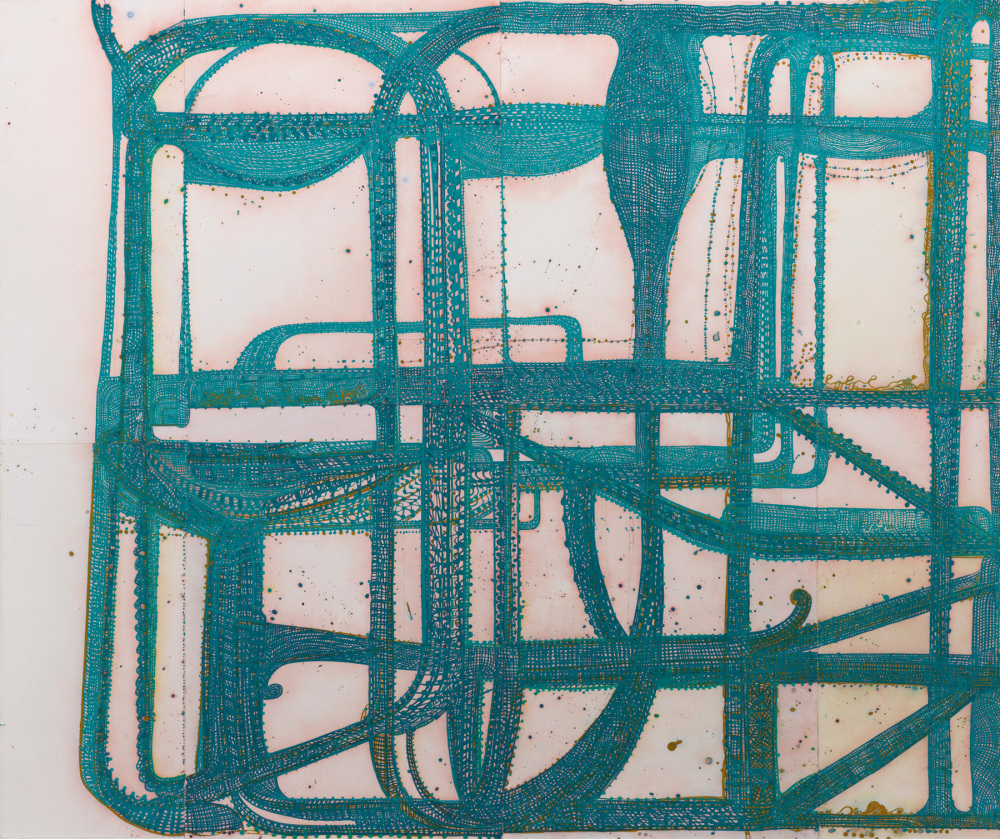

Sharon Horvath, Your Blue Loom, for Martin Ramirez, 2007, Pigment, ink and polymer on paper on canvas, 64 x 76 inches. (BP#1495)

By Vicky Lowry

"Life is complicated, isn't it?" Sharon Horvath is explaining her deeply personal approach to the arresting paintings she creates in her ground-floor studio at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, a giant industrial park on a site dating back to the early 1800s, where American warships once were built.

Horvath's paintings are complicated too. Suffused with brilliant, often startling hues, they are labyrinths of lines and layers that unfold slowly to reveal bits and pieces both recognizable and mysterious. A baseball diamond floats above an antique black bed—or is it a roller coaster? A pale, peaceful landscape runs like a movie inside the shape of a rearview mirror. An electric night sky, glittering with stars, is anchored by a network of hatching— linear lanes of infrastructure that recall the rusted-out buildings and new scaffolding that stand shoulder to shoulder beyond her studio window. The overall effect, whether painted on a canvas 10 inches square or one seven feet wide, is as intimate as an embrace.

"It's the layering and texturing that make you want to come up close," says Brooke Anderson, deputy director for curatorial planning at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Anderson discovered Horvath's work at a 2009 solo show launching Lori Bookstein's new gallery in Manhattan's Chelsea district. The artist was just moving into large-scale paintings; her method is so considered and minutely detailed—Anderson describes her paintings as "seriously wrought works"—it can take Horvath years to complete a single large canvas. At that inaugural show, the bigger pieces sold out immediately.

She begins each work by almost unconsciously making what she calls blind drawings, pencil marks on sheets of paper, while kneeling on her studio floor, sitting on the beach, or most frequently driving. (For a New York City resident she spends an inordinate amount of time behind the wheel, commuting between her home in Queens, her Brooklyn studio, and her teaching job at Westchester's Purchase College, along with frequent treks to her hometown of Cleveland.) After these initial scribbles, Horvath adds and sometimes subtracts layers of images—shapes that can echo such familiar things as textiles and furniture but are sometimes pure abstraction—until she is ready to tackle larger versions.

Horvath was probably destined to become an artist. Her parents met as students at the Cleveland Institute of Art; her father was a painter and her mother was a ceramist and weaver. When Horvath found herself painting in her father's studio at the age of 16, she recalls thinking, "Maybe this art thing is important to me too." A series of paintings featuring looms—including the mesmerizing 2007 work Your Blue Loom, for Martin Ramirez—holds an emotional clue to her art-filled childhood: "My first memory was of a room-size contraption that had all these moving parts, and later I realized that I was probably sitting at my mother's loom."

Elemental issues are at the heart of her work: love, loss—and baseball. Diamonds began appearing in her drawings in 2001, when her son, Paulus, started playing Little League. Attending a Mets game in the wake of the World Trade Center attacks also made a mark. "The baseball games right after 9/11 were very emotional," she explains, "because it was an occasion—possibly the first one— for the amassing of a group of New Yorkers in a vast public space. We don't have a 'mall' for public gatherings like Washington, D.C., has, just Central Park and baseball stadiums.

Now, she says, she's got sex on her mind. "After my father died [in 2010], all I thought about was death. Then a switch flipped and all I could think about was sex." For a new series called lovelife, she's painting lovers—"how they hold each other and let go"—inspired in part by a book of antique Japanese erotic prints. "I want to turn things inside out or upside down and show it. That mystery is what we live for," she says. "I don't trust the way things look; I trust the way they feel—figures intertwined, attached, letting go. Not all paintings speak to feeling. Mine do."