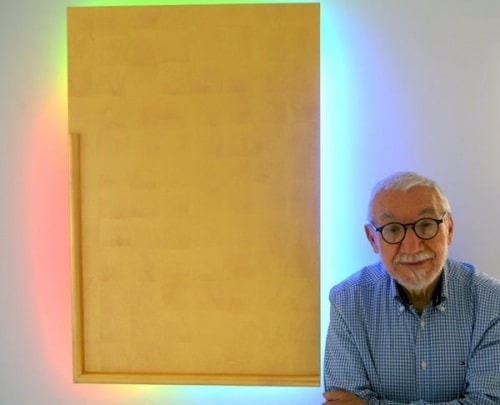

Eleni Mylonas, via Lori Bookstein Fine Art

Stephen Antonakos, in an undated photograph with one of his works, created abstract sculptures distinguished by vibrant colors and sinuous lines.

His medium was light; his materials included glass, an electrical charge and Element No. 10 on the periodic table. The result was a series of abstract sculptures that illuminated indoor and outdoor spaces in cities around the globe, instantly recognizable for their vibrant colors and sinuous lines.

Stephen Antonakos, the sculptor behind those works, died on Aug. 17 at 86. Half a century ago, he became one of the first people to usher neon out of the world of HOT L and into the realm of fine art.

His work, which encompasses public-art installations and pieces in the collections of the world’s foremost museums, is leagues apart from the commercial signage that until the late 20th century was neon’s fundamental expression.

Mr. Antonakos used neon as a painter uses paint. Minimalist, with fluid lines and saturated colors that recall Matisse, his art has appeared in spaces as diverse as airports in Atlanta, Milwaukee and Bari, Italy; metro stations in Boston, Baltimore, Detroit and Athens; a power station in Tel Aviv; and a police station in Chicago.

Two of his installations have long been familiar to New Yorkers: “Neon for 42nd Street” and “Neon for the 59th Street Marine Transfer Station.”

“Neon for 42nd Street,” installed in 1981 on the outside of a building between 9th and 10th Avenues and since taken down, comprised nested arcs of red and blue. Together they formed a glowing discontinuous spiral that, like much of Mr. Antonakos’s work, exploits the haunting possibilities of incomplete geometry.

In the 59th Street piece, erected in 1990 and still standing, Mr. Antonakos outlined the facade of a shipping terminal on the Hudson River at which New York City’s trash is transferred to barges.

Elsewhere, his installations include “Four Walls for Atlanta Hartsfield Airport” (1980) and “Chapel of the Heavenly Ladder,” exhibited at the 1997 Venice Biennale. In that work, rooted in Mr. Antonakos’s Greek Orthodox faith, he built an entire meditative room of rusted iron, suffusing it gently with neon light.

His other work includes drawings, a series of unusual pillows and a set of mysterious, carefully wrapped packages that passed between him and his friends in the 1970s, many of which — by design — remain unopened.

What united Mr. Antonakos’s diverse output was his abiding concern with illumination, incompletion and an almost mystical spirituality that is manifest in everything from his overtly religious pieces to the grip that an unopened box has on the imagination.

Stephen Antonakos was born on Nov. 1, 1926, in Agios Nikolaos, a mountain village in Greece, south of Sparta. His family moved to New York when he was 4.

After graduating from Fort Hamilton High School in the Bay Ridge section of Brooklyn, he served from 1945 to 1947 with an Army artillery unit in the Philippines. He later attended the New York State Institute of Applied Arts and Sciences in Brooklyn and began his career as a commercial illustrator.

His own work included an early-1960s series of pillows that married cloth, text, metal (including plumbing pipes and nails) and other found objects. The last pillow in the series incorporated the word “DREAM” in neon, and with that, Mr. Antonakos found his calling.

To study the rich possibilities of the medium, he scoured Times Square at night. His sculptures began life on paper and afterward — in a collaboration between Mr. Antonakos and the industrial fabricators who bent the tubes to his precise specifications — took shape in lighted glass.

In later pieces, Mr. Antonakos laid neon lights behind painted canvases, or behind panels leafed in silver or gold. The technique bathed each piece in a glowing halo, like those illuminating the figures in Byzantine icon paintings, a tradition that long fascinated him.

His work is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim Museum and the Whitney Museum of American Art in Manhattan; the Brooklyn Museum; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; and elsewhere.

Mr. Antonakos’s first marriage ended in divorce. His survivors include his second wife, Naomi Spector Antonakos, who confirmed her husband’s death, in Manhattan, from complications of heart surgery; a son, Stephen B. Antonakos, from his first marriage; and a daughter, Evangelia Antonakos, from his marriage to Ms. Spector.

In the early 1970s, wanting to expand his repertory, Mr. Antonakos asked scores of friends to mail him packages. Among those who responded were the artists Robert Ryman, Sol LeWitt and Christo, no slouch when it came to wrapping things.

What Mr. Antonakos did not tell them was that he planned never to open the packages — he simply exhibited them, wrappings and all. Whether anyone sent perishable material is unrecorded.

Mr. Antonakos then reciprocated by sending meticulously wrapped parcels to a few dozen friends. These parcels, which contained unspecified items of great personal significance to him, came with strict instructions as to when the recipient could open them: some were to be opened in a far-off year, like 2000; others on Mr. Antonakos’s death; still others, never.

The project became a de facto performance piece about yearning, distance, memory and — as things turned out — elusiveness.

One of those who received a parcel was the art critic Irving Sandler, author of the 1999 book “Antonakos.” Decades ago, Mr. Antonakos sent him a flat package measuring about 18 by 24 inches. It was to remain sealed until Mr. Antonakos’s death.

In a telephone interview, Mr. Sandler was asked whether he now planned to open it.

“Yes,” he replied. “When we find it. We’re going to have to look for it.”